The Black Coronet: The History of the Rolex Cellini

Since the 1960s, the Rolex Cellini has stood out amongst the Rolex range, as rather than being a tool, it is designed purely with elegance and sophistication in mind. Has this black sheep of the Rolex family outstayed its welcome, or is there a place for the Cellini in today’s world?

JOHN NICHOLS

OCTOBER 9, 2020

Rolex, probably the first name that comes to mind when you think of a watch, made its name in the 1920s with reliable, durable tool watches – a stark contrast to the delicate jewellery pieces that were popular at the time.

Released in the 1960s, the Rolex Cellini was a distinct step away from the formula that made the brand a household name. Rather than a purpose-built tool, this was a delicate, black-tie and cocktails timepiece. This week, I’ll take a look at the history of the Cellini and if, in today’s increasingly casual environment, it may be on its way out.

History

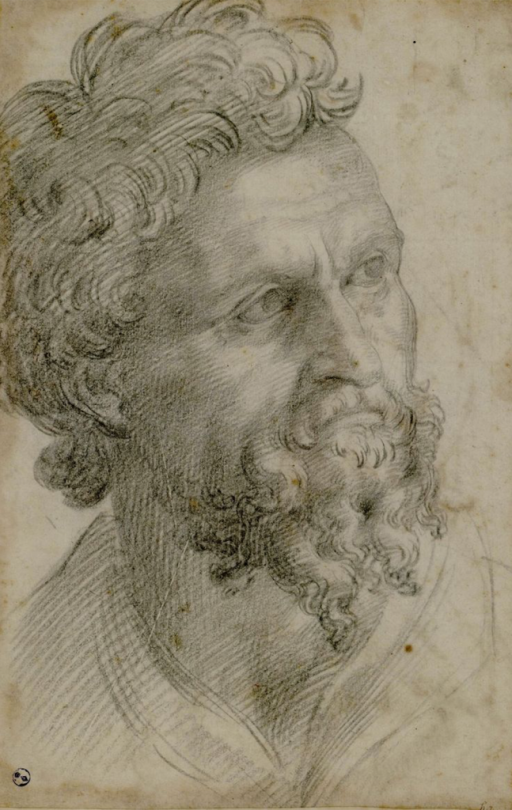

The Cellini line is named after Benvenuto Cellini, a maverick of the 16th century who, amongst many other talents, was a heralded goldsmith and sculptor – a fitting name for Rolex to emblazon upon its line of exclusively gold, sophisticated timepieces.

The first Rolex to be designated as a Cellini is hard to pinpoint, as over the years the moniker has been given to watches with a wide range of designs to signify them as Rolex’s flagship dress watch, unlike more standardized models such as the Submariner or the Daytona.

The brainchild of then Rolex Director Rene-Paul Jeanneret, the idea way to create a dress watch based purely on aesthetics, rather than capability. It was almost a way to assert their dominance – we became kings of the industry designing tool watches that reigned over your dress pieces, now watch us beat you at your own game.

As such, a number of distinct models have come and gone over the years. No Cellini has ever used Rolex’s standard Oyster case, and the majority of models have featured hand-wound movements, rather than the Perpetual automatic movements pioneered by the brand in the 1930s.

That’s not to say that every Cellini has been an understated, starched-collar endeavour. The late 60s and early 70s brought a period of extravagant designs, one such being the Rolex King Midas, released in 1963.

Asymmetrical, with an integrated bracelet and being the first Rolex to have a sapphire crystal, this piece certainly turned heads. This was also the first Rolex to have a left-hand version, owing to the unique case shape, and earned the distinction of being the heaviest solid gold watch money could buy at the time – certainly the most expensive in Rolex’s catalogue.

Released in 1964 with a 1,000-piece limited run, it was quickly picked up by one Elvis Presley. Garish, loud and with a rebellious nature, it was the perfect fit for The King.

With an unusual case shape, angular design and integrated bracelet, if rumour is to believed, this watch was penned by a man who was then a rising star in the industry, and would eventually become arguably the most important figure in modern watchmaking – Gérald Genta.

The late 70s saw a move away from flamboyance and towards understated refinement. Mid-30mm sizing, elegant curves and modest aesthetics were the name of the game, with models such as the Cestello and the wonderfully suave Danaos coming into the fray.

The Cellini line trundled along with no major developments until the mid-2000’s, with the return of the Cellini Prince – a rectangular-based piece with a running seconds sub-dial, inspired by a watch from the 1920s, purportedly a favourite of Al Capone.

These re-released models, in white gold, yellow gold and Rolex’s proprietary Everose, are distinct in that they include display casebacks – a rare departure from Rolex’s solid-back norm.

The Cellini Today

The last time the base model was given an update was in 2014, with the Cellini being one of the notable exceptions to the overhaul of almost every other Rolex model in the last few years.

There are currently four models in the Cellini line, all with the same 18ct white or Everose polished gold case; the time-only Cellini Time at £12,200, the date sub-dial, guilloche dial Cellini Date at £14,300, the self-explanatory Cellini Dual Time at £15,600, and the 2017 Cellini Moonphase at £21,450.

All four models have similar movements, each being an automatic with a Parachrom hairspring, 48 hours of power reserve and accurate to +2/-2 sec/day – Calibres 3132 in the Time, 3165 in the Date, 3180 in the Dual Time, and 3195 in the Moonphase.

An automatic movement is a strange choice for a dress watch, but is in line with Rolex’s current philosophy of fitting all of their base models with automatic movements for wearer convenience.

The Cellini Moonphase is particularly notable, as it’s the first Rolex in over 60 years to fit this historic complication.

Competition

To assess the value proposition, let’s look at three dressy time-only watches and three dressy moonphases, to see what similar money might be able to get you.

For a time-only dress watch, Grand Seiko have the SBGY003. Priced at £7,300 and powered by the Spring Drive 9R31, it’s both almost £5,000 cheaper than the Cellini Time and packs a further 24 hours of power reserve. Of course, being a Spring Drive, it is also more accurate at +15/-15 sec/month.

If you’d prefer some true Glashütte watchmaking, A. Lange & Söhne have the Saxonia and Saxonia Thin, priced at £13,900 and £13,600 respectively. Both feature true-to-origin manual-wind movements… with the latter featuring the innovative L093.1 movement, managing 72 hours of power reserve in a movement only 2.9mm thick.

Stepping into the traditional holy trinity of watchmaking, Vacheron Constantin put forward the Patrimony Manual-Winding. Whilst over £5,000 more expensive at £17,500, you get a well-decorated hand-winding movement entrusted with the Geneva Seal – a sign of the very pinnacle of watchmaking brilliance.

Moving on to moonphase complications, Jaeger-LeCoultre have the classically-styled Master Ultra Thin Moon at almost £5,000 less – £16,500. Whilst the automatic 925/1 movement offers 10 fewer hours of power reserve, the watch includes a discrete date indicator around the moonphase window.

For an extra £500 (£17,000), Cartier offer the cushion-cased Drive de Cartier Moon Phases. Featuring identical reported power reserve to the Cellini Moonphase, this is for those who want a little more expression from their dress watch whilst remaining faithful to their purpose.

It’s back to A. Lange & Söhne we go for the third and final option, as for over £6,000 more, we have the Saxonia Moon Phase at just less than £28,000. With a solid silver dial, solid gold indices and rhodiumed gold hands within an 18k white gold case, plus an outsized date automatic movement with 72-hours of power reserve, we’re breaching entry-level haute horlogerie with this piece.

With both the Cellini Time and Cellini Moonphase, very tempting alternatives are available for a few thousand less, as well as objectively better timepieces for a few thousand more. Choosing between them, as with any watch, will come down to what is important to you. Power reserve? A hand-wound movement? The lure of the coronet?

My Thoughts

To me, the Cellini screams of wasted potential. Here we have the world’s most well-known luxury watch brand trying to grab a stake in the lucrative dress watch market, and with their resources, you would anticipate them being able to pull it out of the bag.

However, there’s a lack of restraint in the design, like they couldn’t help themselves but to add little details and ornamentation, whereas established dress watch brands have both the knowledge and experience to execute a simple piece.

Take the Vacheron Constantin Patrimony for example. A plain, polished white gold case, plain dial and hands, slightly oversized at 40mm but with a hand-wound movement – it’s an exercise in elegant, sophisticated discipline, arguably a much more difficult, and highly impressive, feat to achieve.

The Cellini sticks out like a sore thumb in the current Rolex lineup. The Swiss giant puts a lot of time, effort and resources behind promoting their other models, but the Cellini doesn’t get anywhere close to the same treatment, and it shows.

The intra-brand competition doesn’t help matters. Whilst many would argue that the Datejust is a sports watch, I imagine those considering a dressier Rolex are more likely to purchase a Datejust than a Cellini Time, especially with the Datejust 41 being over £1,500 less, and the Datejust 36 almost £3,500 cheaper.

Traditionalists believe that the ideal dress watch should be hand-wound, time-only, and less than 38mm in diameter. The Cellini fails in all three of these, and with the domed & fluted bezel as well as the numerals on the dial, it also misses the mark in the most important factor for a dress watch – being understated.

As shown in the comparison watches chosen above, I believe you can get much better value for money than with a watch in the Cellini range. A Submariner, a Datejust, a Daytona? All have strong value propositions, but the Cellini just falls short of the lofty heights of its contemporaries.

In Conclusion

Is time up for the Cellini? It’s tough to say since Rolex would never release their exact sales figures, but I wouldn’t be surprised if a few higher-ups were casting doubts on the current state of the line.

The Cellini models are in serious need of a shake up to bring them bang up to date and able to compete on a more even footing with similarly-priced, competing dress watches from the likes of Grand Seiko, A. Lange & Söhne and Cartier.

Even with the Cellini in its current state, should Rolex decide to call it a day with its dress watch endeavours, it would be a crying shame. The Cellini has always been about Rolex broadening its horizons and taking on its competitors at their own game, and there’s a sense of brashness, belief and world-beating confidence that would be lost with the removal of the line.

Whatever happens with the Cellini line in future, it’ll always be seen as the black sheep of the Rolex family, but looking back at the history of the model, the intriguing designs it has spawned, and the touch of flair it’s given to countless individuals over the years, being the black sheep doesn’t necessarily have to be a bad thing.

Published October 9, 2020.